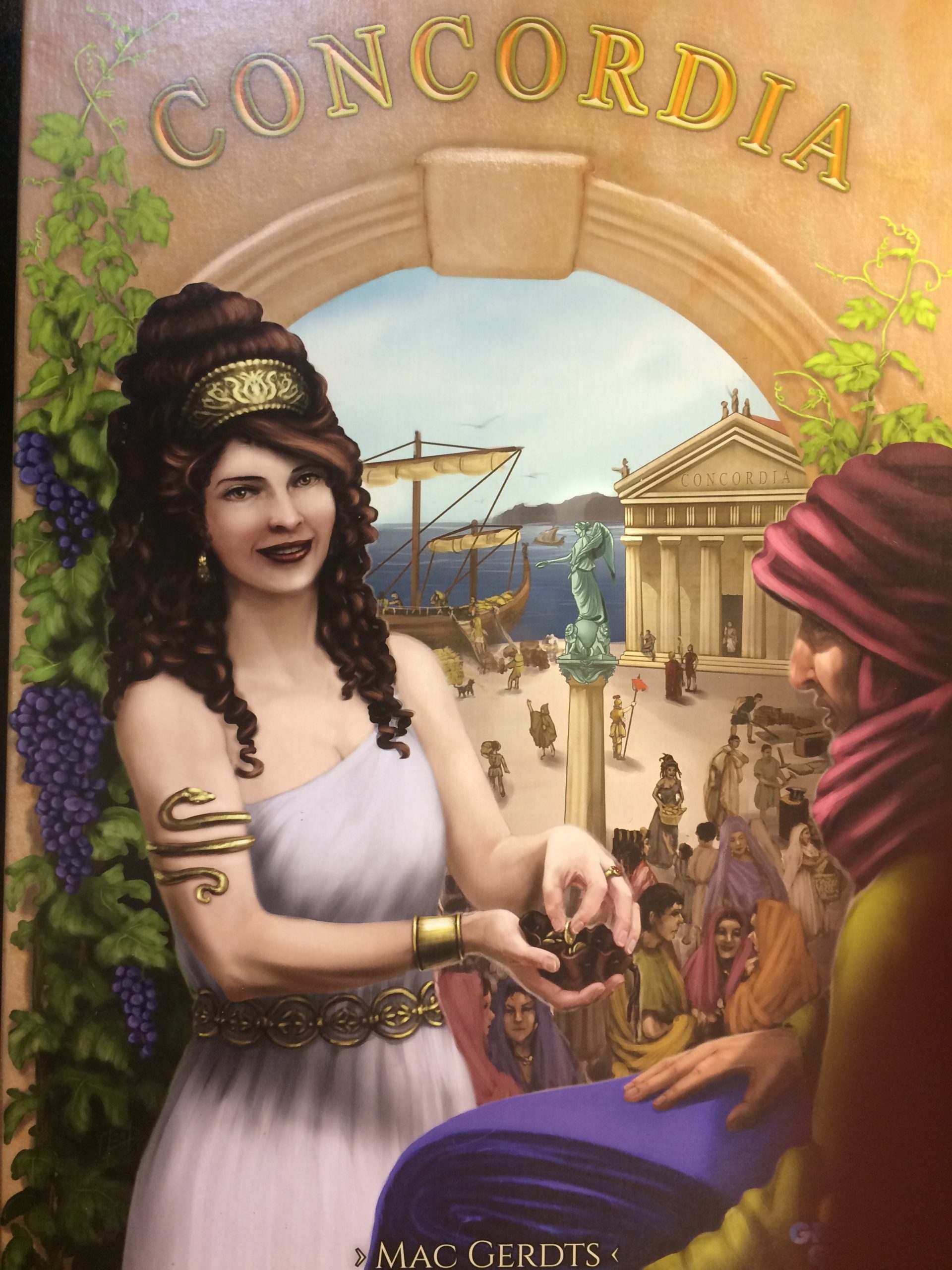

Game:Concordia

Year: 2013

Designer: Mac Gerdts

Publisher: Rio Grande Games

Key Details: 2–5 players, 120–180 minutes

Gameplay Score: 8/10

Theme Score: 6/10

Overview of Play:

This game plays 3–5 players, and scales pretty well with any number, in part because the map is two-sided (the Mediterranean, or ‘Imperium,’ side is used for 3–5, the ‘Italia’ side for 2–4). This game takes way longer than the 90 minutes that the box says, especially if you play with 5. If your group knew it well, though, you can definitely get it down to 2 hours.

Each player controls a group of colonists and ships that they send around the Mediterranean (or Italy) to build houses and collect goods. There are different types of goods, and it’s more expensive to build in cities that provide more valuable goods—and in cities where other players have already built. Since good types are assigned randomly, the map changes with each play.

The main mechanic is managing a hand of cards. Each player starts with an identical hand of cards, and chooses one of those cards to play each turn. Each card allows you to perform a different action, including moving and building, collecting goods in a particular province, trading some of your goods for other types or money, buying new cards, or getting all of your cards back.

Many of the cards you buy are more powerful versions of the cards you start with, and every card is associated with one of six gods. Each god in turn factors into scoring. For instance, Saturnus cards give a player 1 VP for each province they have a house in. Thus, you’re trying to balance what the cards do when you play them with how they will affect the end-of-game scoring. In turn, these cards will shape your goals. If you have Mars, for example, you benefit from having more colonists, so you may want to play the Tribune card more, since it allows you to create more colonists.

So, the game has deck-building aspects, but it’s not a deck builder. It’s really a game of resource management, where you’re managing not only your goods and money, but also your most valuable resource: your cards (think of it as a hand-builder). The game boils down to who can get the most efficient use out of their cards.

Note: I’m only reviewing the base game here. There are a bunch of expansions for this, but I haven’t played any of them, and I’ve heard/read mixed things. I like the base game enough that I don’t feel any need to add expansions (to be fair, though, in general I’m not a fan of expansions for board games).

Thoughts on Use of Theme:

Like a lot of games, the theme comes more from the components than from the gameplay itself, and there’s a lot of great attention to detail here. There are a lot of familiar elements here, such as the use of ‘Æ’ for ‘AE’ and ‘V’ for ‘U’ in the names of cities and provinces (which are all in capital letters). Like so many Roman-themed games, the coins are called sestercii, and marked with Roman numerals.

But most striking are the big, beautiful maps of the gameboard. The 2–4 player map shows Italy, divided into 9 provinces, roughly corresponding to the emperor Augustus’ divisions into regions, though Samnium and Picenum have been replaced by Corsica and Silicia. I don’t have a problem with these kinds of changes at all, since adding the latter two helps spread out the map and encourage players to choose both sea and land colonists.

The map for 3–5 players represents the high Roman empire, with the latest cities being Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter, founded mid to late 1stcentury CE) and Napoca (in ancient Dacia, modern Romania, founded in the early 2ndcentury, after Trajan’s conquest). The provinces are all real provinces, with only minor issues such as there being only one Mauretania, even though there were two at the time.

Although none of these details affects gameplay in any way, the game includes a very nice booklet that provides an impressive amount of information about the provinces on the ‘Imperium’ side of the map (e.g., it discusses the creation of the Limes Tripolitanus in Libya). It also provides the modern equivalents to the ancient cities, and gives their current country and population (cities such as Leptis Magna, Memphis, and Petra are noted as being “in ruins”). For whatever reason, there is no such information on the regions or cities on the ‘Italia’ side of the board.

Like I said, none of this information affects the gameplay at all, but it is a nice touch, and not something the company needed to put in; they would, of course, have saved money by not including it. It’s a nice attempt to give the game substance, and one could learn a decent amount about the areas shown in the game by reading it.

The booklet also provides information about the gods used in the game: Vesta, Jupiter, Saturnus, Mercurius, Mars, Minerva, Concordia. With the exception of Jupiter, the gods get their Latin names (e.g. ‘Mercurius’ instead of ‘Mercury’). I assume that Jupiter is the exception because ‘Iuppiter’ may have seemed just a bit too different to be easily understood.

Unlike with the provinces, where the details do not matter for gameplay, here the details are skewed somewhat to connect the gods to their roles in scoring. For instance, “SATURNUS is the divinity of sowing and agriculture. He rewards the virtue of agriculture demonstrated by the number of provinces in which players have built houses.” It is true that Saturn is connected with sowing and agriculture (Latin sator means ‘sower’ or ‘planter’), but connecting this with houses doesn’t really make any particular sense. Vesta would have been better suited here, or perhaps the Penates—though they are likely not well enough known.

A missed opportunity is Juno, especially with her cult epithet Moneta, ‘She Who Warns.’ Because the first mint in Rome was next to her temple, we get the word ‘money’ from this title (the etymology is even clearer in the adjective ‘monetary’).

The cards themselves all have Latin names (or Anglicized forms of them), but don’t always have any meaningful connection. For instance, while the ‘Mercator’ (‘Merchant’) card gives you money and allows you to buy and sell goods, the Tribune doesn’t really have anything to do with legislation or vetoes, but allows you to get your cards back and purchase another colonist. A nice touch, however, is that the Consul card is in many ways the most powerful card—though by this time the consuls weren’t anywhere near as powerful as they had been during the Republic.

The goods add very little flavor to the game, being simply brick, food, tool, wine, and cloth. Because the goods are placed somewhat randomly every game, there would really be no way to use more area-specific goods—especially given the game’s two maps. There is a hint, however, that the cloth is something special. First, the wooden pieces for it are purple, suggesting the famous Tyrian dye connected with ancient royalty and Roman senators. Similarly, cloth is the most expensive good, further suggesting its luxury status. Again, it doesn’t affect the game in any real way, but it’s clear that there was some thought here.

The back of the box advertises that “CONCORDIA is a peaceful strategy game of economic development in Roman times,” which is appropriate for a game whose Latin name means ‘harmony.’ Like a lot of so-called Euro games, Concordia advertises itself as not using any dice or luck, making it a game of pure strategy.

Also, like a lot of Euros, it doesn’t offer any way to attack your opponents directly. You can try to build in cities before they get there (thereby making it more expensive for them to build there), or you can try to buy a particular card before they do, but you can’t really do anything to stop someone’s progress (also, as with many Euros, it is difficult to have any sense of the score until the game is over). People who don’t like cutthroat games should like the overall harmonious vibe of this one.

But this emphasis on the peaceful nature of the game, as stressed by its name, sits poorly with a game based on colonization. Having a map called ‘Imperium’ (‘Empire’) and having pieces be called colonists hints at the violence behind Rome’s expansion without addressing it. This hits on a fundamental issue with a lot of Eurogames, in which the competition between players is peaceful, thereby eliding the violence at the heart of the source material. An excellent discussion of this can be found at:

There are few hints at the violence underlying the realities of the Roman situation, the most obvious being the use of the term ‘colonist’ for the players’ pieces. The Praetor card also hints at this, since playing it causes the houses in a given province to produce goods to benefit the players, all of whose colonists start out in Rome. It is a small reminder that the provinces of the Empire produce goods to benefit those in the center (and is thematic in the sense that, at some points of Roman history, praetors oversaw certain provinces).

In addition to being shallow, then, the theme whitewashes or even ignores the violence underpinning the game’s scenario. For me, this doesn’t ruin the game or make me not want to play it, but players should be aware of the sanitized version of history they so often get in Eurogames.

Overall Thoughts: Despite the game’s somewhat disingenuous use of theme, I really enjoy playing Concordia. When I first got it, not too long after it came out, my group played it a lot, and we come back to it in spurts. It’s relatively easy to learn, but has a good amount of replay value. There is a lot of thought that can go into how you play your cards, and the lack of conflict between players makes for a pretty laid-back playing experience.

One of the distinguishing features of this game is how beautiful it is. The art is colorful, and fits the theme, and the wooden pieces for the various goods have different shapes, and bright colors. When everything is laid out, it’s a pretty sight.

My reason for not giving it a higher score is that there’s not enough player interaction for me. As the game progresses, it can start to feel like everyone is playing their own game, and it’s easy (especially for novice players) to pretty much ignore everyone else. If you think you’re falling behind—and it’s hard to tell who’s in the lead, since you only score at the end—there’s not much you can do to slow others down. Some people like this kind of no-identifiable-leader kind of game, but it’s not my cup of tea; it encourages more of the head-down approach than I find unappealing.

I like deck-builders and card games, and this scratches some of those same itches. But by combining traditional Euro elements with deck-building elements, it also doubles up on the biggest problem I have with both types of game, namely that it can get boring to sit there while other people take their turns.

Still, it’s a fun game, and beautiful to look at. The core hand-management mechanic is great, and keeps me coming back.